Climate-Smart District Heating

High-Temperature Heat Pump Utilizes Waste Heat from Cooling Systems

At Potsdamer Platz, underneath state-of-the-art high-rise buildings, shopping centres, and very busy roads, lies an underground system that ensures comfortable temperatures for the entire district. Since 1997, a cooling network has been efficiently delivering locally produced cooling power to over 12,000 offices, 1,000 housing units, and numerous cultural facilities, hotels, and administrative headquarters at the heart of Berlin. Coinciding with the network’s 25th anniversary, a new project has now been initiated which aims to use waste heat from the cooling plant to generate climate-smart district heating. To bring this about, assembly work has now begun on a high-temperature heat pump. During operation, the system will replace heat from natural gas, saving around 3.2 million cubic metres of gas. This will result in a reduction in CO2 emissions of up to 6,500 tonnes per year.

Advancing the transformation of the heating sector and securing the heating supply

Project partners Vattenfall Wärme Berlin and Siemens Energy aim to trial the practical application of this innovative technology in the Qwark3 research project. (The German acronym “Qwark” refers to the coupling of district heating, power, and cooling.) The goal is to implement a high-temperature heat pump to provide residents and commercial customers with efficient, climate-smart heating in the future while simultaneously reducing the amount of cooling water used in the cooling plant. The system will be the first in its performance class worldwide to generate temperatures of up to 120 degrees Celsius.

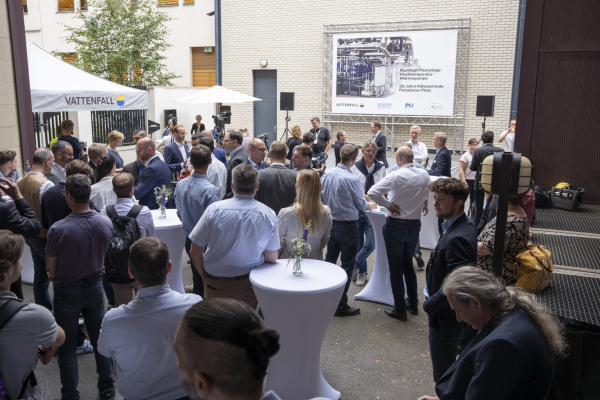

The topping-out ceremony for the system, which was held at the start of July in Berlin and doubled as the anniversary celebration for the cooling plant, was attended by representatives from the project partners and the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK), which is providing funding of approximately € 4.4 million for the project.

“Research results that demonstrate a technology’s suitability for practical use can serve as a model for others,” said Dr. Wolfgang Langen, head of the IIC6 energy research division at the BMWK. “The partners in this demonstration project, Vattenfall Wärme Berlin and Siemens Energy, aim to show how the energy transition can be achieved through intelligent sector coupling with innovative heat-pump technology for district heating.”

From heating to cooling and back again

The process of generating cooling power at Potsdamer Platz produces waste heat, which is removed via a water circuit and dissipated into the surrounding environment through cooling towers. This heat is usable; however, the return water is not hot enough to be fed into Berlin’s district heating network directly. This is where the high-temperature heat pump comes in. It raises the temperature of the water to a higher level – between 80 and 120 degrees Celsius – so that it can be fed into the district heating network as required. The electricity for operating the heat pump comes from renewable sources.

With 8 megawatts of thermal power, the high-temperature heat pump generates total annual heat of up to 55 gigawatt hours. This is enough to provide hot water for 30,000 households in summer, and heating for 3,000 households in winter. The key to the system’s success is a novel refrigerant which is to be used in the high-temperature heat pump. The technology will not only make it possible to use the waste heat, but will also enable a more efficient cooling supply. The project partners estimate that this will lead to annual savings of 6,500 tonnes of CO2 and approximately 120,000 cubic metres of cooling water.

District cooling at Potsdamer Platz – How it works

District cooling at Potsdamer Platz is provided though a centralized cooling supply that works more efficiently than decentralized facilities in individual buildings. Large absorption and compression cooling systems in the cooling plant cool water to a temperature of 6 degrees Celsius. To do so, the absorption chillers use urban heat from Berlin Mitte’s combined heat and power plant. The compression chillers are operated using electricity. The cold water flows through an underground district cooling network to various consumers in offices, housing units, and other buildings. There, the water cools rooms and is reheated to around 12 degrees Celsius. It then flows back to the cooling plant through parallel pipelines, where it is cooled again. The cooling systems are managed by a Berlin-based heating control room. Depending on how much energy is available, cooling power generation is adapted flexibly in coordination with the urban heating system.

more (in german)“For the past 25 years, the cooling plant has served as a model for forward-looking district planning. It is a concept that is still proving successful today and shows what we can achieve when policymakers, scientists, and industry come together to plan and implement,” says Tanja Wielgoß, CEO of Vattenfall Wärme AG. “With the new high-temperature heat pump, this novel energy concept has now become even more innovative. The Qwark3 project is another important building block on the path to achieving net-zero heat production for our urban heating system by 2040.”

Qwark3: Practical application will deliver valuable findings

The project is scheduled to run until mid-2025. During this time, the partners aim to gather practical experience and thus gain important insights into the use of high-temperature heat pumps. Reliable findings are particularly important for implementing the transformation of the heating sector. According to plans, the system will be put into operation this November. This will be followed by a three-year monitoring phase. (ks)

Heat pumps: Efficient use of ambient heat

Even on a small scale, heat pumps are particularly efficient: depending on the design, a commercially available system capable of heating a single-family home, for example, can produce 8,000 kilowatt hours of heat from around 2,000 kilowatt hours of electricity. This is possible because heat pumps take heat from ambient air, the ground, or other sources and only use electricity to upgrade that heat to achieve a higher heat output. Fossil-fuel-based heating systems consume around 800 litres of heating oil or 800 cubic metres of gas to produce the same heat output.

Siemens Energy Global GmbH & Co. KG

www.siemens-energy.com/de/

Tel.: +49 (911) 6505 6505

contact@siemens-energy.com